Part of the fascination I have for traditional folk songs is the way in which they humble the singer. As a singer/songwriter, I spent years thinking about the ways in which a song represents the self – a snapshot or meditation on the writer in that moment.

What grabbed me about traditional song was how much the focus returned to the song itself. For the brief period that it lives in a singer’s repertoire, that person is essentially taking care of it, possibly nurturing it a little – shepherding it onward so that others may sing it afterwards. It exists before the singer, in the presence of the singer and then again at such a time when the singer no longer performs.

As such, the song has a story, outside of its central narrative, that is continuously being written. The story of its existence – where it was sung, by who, to who and why – is absolutely enthralling to me, and is as important a part of the performance as the act of singing it.

So, here’s a song and its story, as I’ve come to know it, both of which I’ve grown to love. Those that have seen me perform ‘Holly Ho’ live will know how much I enjoy relating the tales that surround it. It seems to me to perfectly answer that finicky old question, “What is a folk song?” Let me explain why.

Holly Ho – a bit of background

‘Holly Ho’ fell into my lap in early February, 2019. I was sitting in the big green chair that takes up a corner of our back room, trying desperately to stay warm. During the research for my Midlife album, my absolute bible was Roy Palmer’s Songs of the Midlands. I combed through it more times than I can recall, and had assumed that I’d learnt all the songs I was ever going to get from it.

On this day, I thumbed through it again, alighting at last on the very final song in the book. Why I hadn’t picked up on it before, I don’t know. For what ever reason, however, on this occasion one verse leapt from the page:

Now I said to me sweetheart the other day,

“What dost thee want for thy birthday?”

She answered, “Diamonds”, so straight there and then

I gave her the Ace, the King, Queen, Jack and Ten”

I’ve since sung this in public many times, and without fail it gets a laugh. However, it was the familiarity of the vernacular that grabbed me. It felt like a song that belonged to people I had known in my younger days, back in the Midlands. And sure enough, when I turned to the research notes…

“Sung by Mr Joe Mallen, Halesowen; collected by Elizabeth Thomson, 1958. Joe Mallen, who was known as Joe the Chainsmith, once kept a public house in Cradley Heath, where this song was very popular. The customers used to add their own verses.”

Not that I was frequenting public houses in Cradley in 1958, of course. But here was a real sense of this being an organic song sung by local people, none of them professional singers. It grew and morphed of its own accord, lines being shaped and then falling away with time – survival of the fittest in verse form. Wasn’t this the very essence of a folk song? It excited me immensely.

I learnt the song quickly. Melody-wise, there’s not a lot to it, and the verses are short and snappy enough to commit to memory after a couple of times through. Essentially, it entered my repertoire (my period of caring for it) on February 27th, 2019, when I plucked up the courage to give it a go at The Lights in Andover where I was supporting my friend, Jackie Oates. The response was wonderful. There’s are so many punchlines, and it’s real fun as a performer to leave the audience hanging slightly to see if they can work out what those punchlines might be before you sing them. It has since closed every performance I’ve done. It’s the very essence of bonhomie.

Meanwhile, I was interested to see if I could learn anything else about ‘Holly Ho’. I had just a few clues, but they were enough to get my detective senses tingling. I had that name: Joe Mallen. I had the town: Cradley Heath. And, most importantly, I had a new friend…

Holly Ho and Pam Bishop

Anyone who takes an interest in Brummie and Midlands folk songs will come across the name Pam Bishop soon enough. In my case, I recorded one of her melodies as the opening track to Midlife. Shortly after doing so, I received an email from her saying that she was intrigued by my interest in Birmingham songs, and so a correspondence began.

Pam has been involved in Birmingham music since the 1960s, and she continues to run the Trad Arts Team with her partner, Graham Langley, to this day. In folk music terms, her backstory is wonderful. Not only did she run one of the longest-running folk clubs I’ve ever heard of (The Grey Cock Folk Club), but she also collected songs from the legendary Cecilia Costello. She has been involved in the editing of many important books, including Songs of the Midlands (mentioned above), and she recorded songs for Topic Records in the early 70s, specifically on The Wide Midlands. Without Pam, my Midlife album wouldn’t have even occurred to me. I was delighted to make her acquaintance.

I dropped Pam a line back in February to see if she could recall anything else about ‘Holly Ho’. Having been involved in the editing of the book in which I discovered it, she seemed the most obvious first port of call (Roy Palmer is now deceased). I was particularly interested to know if she had any recollection of Elizabeth Thomson, the collector mentioned in Palmer’s notes. The information on Elizabeth’s work as a collector seemed frustratingly limited.

Pam’s initial reply was brief…

“I did know someone called Elizabeth Thomson who might be the same one. She was the daughter of Katharine Thomson, who founded the Clarion Singers in Birmingham. Katharine and I were music editors of the “Songs of the Midlands” book.”

Moments like these are thrilling. I’ve written on this blog before about folk songs being “bridges through time”. Here was yet another wonderful example of that. Pam told me she’d see what else she could uncover, and away she went.

Meanwhile, I had some work to do on old Joe Mallen.

Holly Ho and Joe Mallen

On March 5th, I sent out a series of emails to people who had notable connections with websites and museums dealing with Black Country history. I was keen to know more about this Joe Mallen chap, and whether or not he might’ve been a source of other songs.

So far, I’d managed to scrape together a few further bits of information. I knew from Google searches that Mallen’s pub had been called The Cross Guns, that it had stood on Cradley Road, Cradley Heath, until relatively recently before being converted into housing. A brief biography of Joe exists on the website for St Peter’s Church, also in Cradley, that identifies him as ‘Gentleman’ Joe Mallen, nicknamed after a famed Staffordshire Bull Terrier that he bred called Gentleman Jim. Joe is buried in St Peter’s graveyard, Section J, Row 8, Grave No 101, should you wish to pay your respects.

According to the church’s website, Joe was a chainmaker, born July 11th 1890, who made a name for himself as a breeder of dogs – dog-fighting still being a notable pastime in his youth, although he’s noted as having been involved in breeding for Crufts (more on that later). Married to Lil, they took on the Cross Guns pub which she married while he was out chainmaking.

It’s an interesting point that the song, which we’ve already seen taking on new verses written by the pub regulars each week, should make reference to a strike by, “the lady chainmakers”. Again, this is a bridge in time and a snapshot straight out of the life of Joe Mallen. In 1910, thousands of women chainmakers went on strike for 10 weeks in the Cradley Heath area, campaigning for the right to the minimum wage*. Since ‘Holly Ho’ wasn’t collected until 1958, this would suggest that the song had been making the rounds for some time before Elizabeth Thomson took it down.

In my further quest for a bit of context and background info, I also contacted The Black Country Living Museum. Over a brief exchange of emails with Historical Research Assistant, Simon Briercliffe, I was able to discover that, “Joe Mallen entered Crufts in 1936 with a Staffie called Cross Guns Johnson. He was beaten in the final by another Black Country dog though, with the wonderful named of Vindictive Monty!” I think the dogs’ names alone merit inclusion of this anecdote in Mallen’s story.

Joe’s reputation as a dog-breeder and “general tough nut” was cemented in a 1969 ATV documentary called The Black Country. Here’s a copy I found uploaded to YouTube. It’s likely that his reputation was further enhanced by a chap named Phil Drabble, whose name will be familiar to those with long memories. We’ll get to him shortly.

*Sure enough, within hours of publishing this blog post, the folk singer Rowan Godel contacted me on Facebook to say that she’d sung ‘Holly Ho’ as part of a folk opera called ‘Rouse Ye Women’. Working in conjunction with the legendary John Kirkpatrick, the piece dealt with the aforementioned women chainmakers’ strike. It toured in the spring of 2019. Read Rowan’s blogpost about it here.

The continued tale of Elizabeth Thomson

As good, if not better than her word, Pam Bishop returned with information a week or so after our last correspondence. With her folk collecting hat firmly back on her head, she’d taken herself off to Birmingham Library to see what she could find.

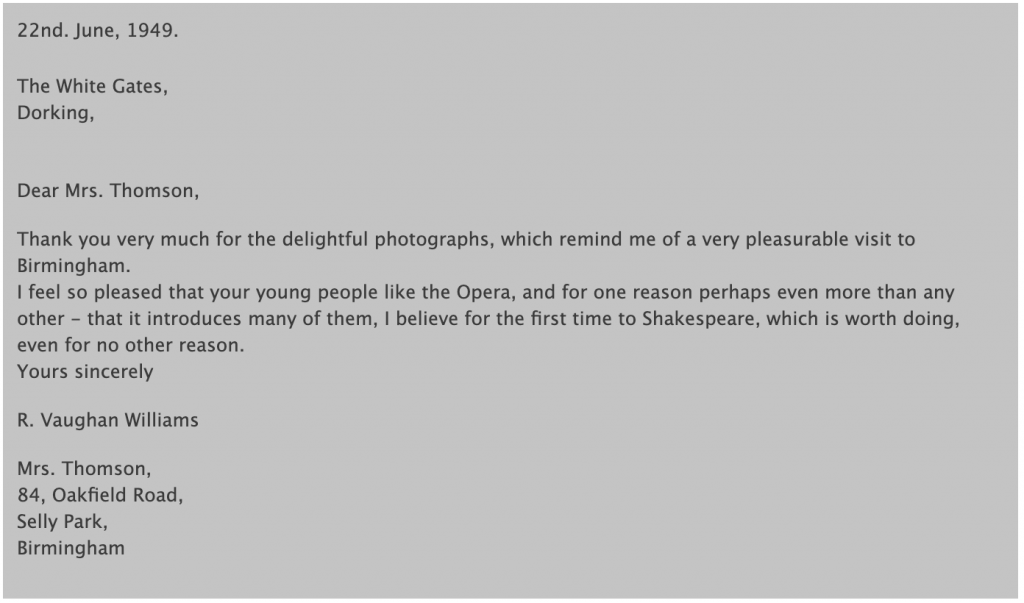

First up, a letter from Ralph Vaughan Williams, suggesting that her search for songs had been on the go for at least a decade before she published her studies and activities in the form of a thesis.

The thesis in question is housed in the Thomson Archive at the Library of Birmingham, and can be viewed on request. Elizabeth Thomson’s interest in industrial songs from Great Britain somehow came to fruition while studying at the University of Prague. Pam Bishop was kind enough to take down some of the information, but it seems that when she arrived at the page documenting the collection of ‘Holly Ho’, she found the page missing. We presume that it perhaps went to Roy Palmer for the editing of the book in which I found the song.

Taken from Pam’s notes, here is Elizabeth Thomson on the discovery of ‘Holly Ho’…

“I have also tried to find out whether there are any local Black Country songs still in existence. On the advice of Phil Drabble, author of books about the Black Country, I went to visit Joe Madden, a 68 year-old chainsmith, who used to keep a public house at Cradley Heath. he and his wife sang many songs to me. Most of them were not local songs, except for one which I have included here. Apparently this song used to be very popular at their pub. All sorts of people joined in, adding verses of their own. This was the only song that had any reference to chainmakers.”

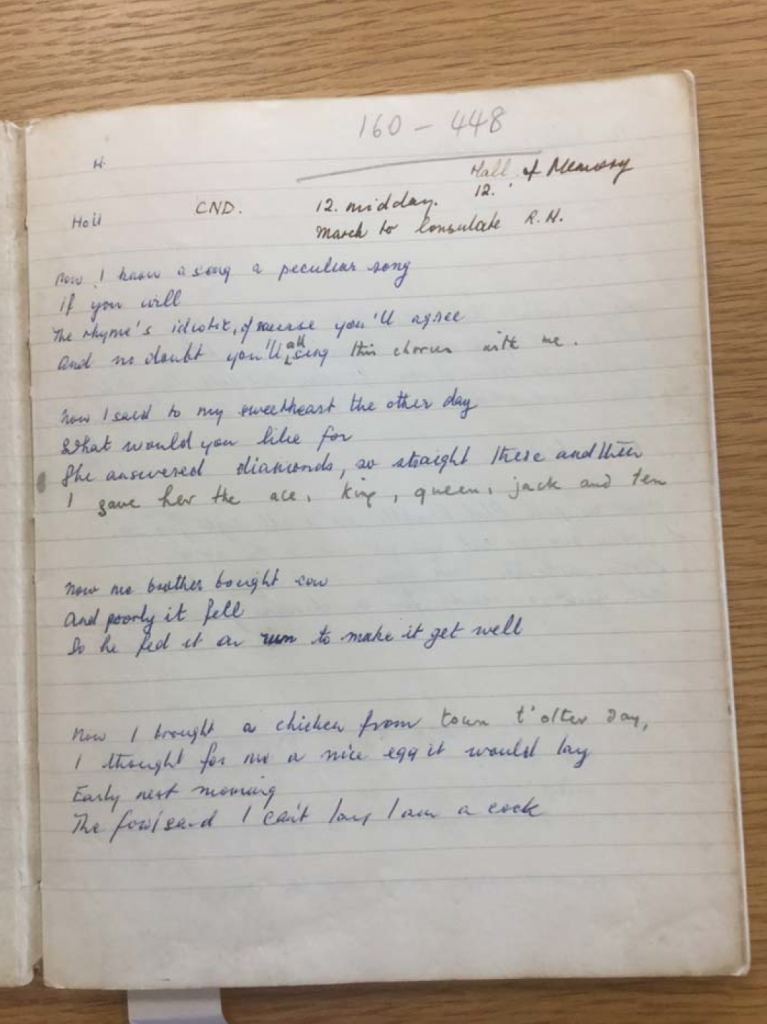

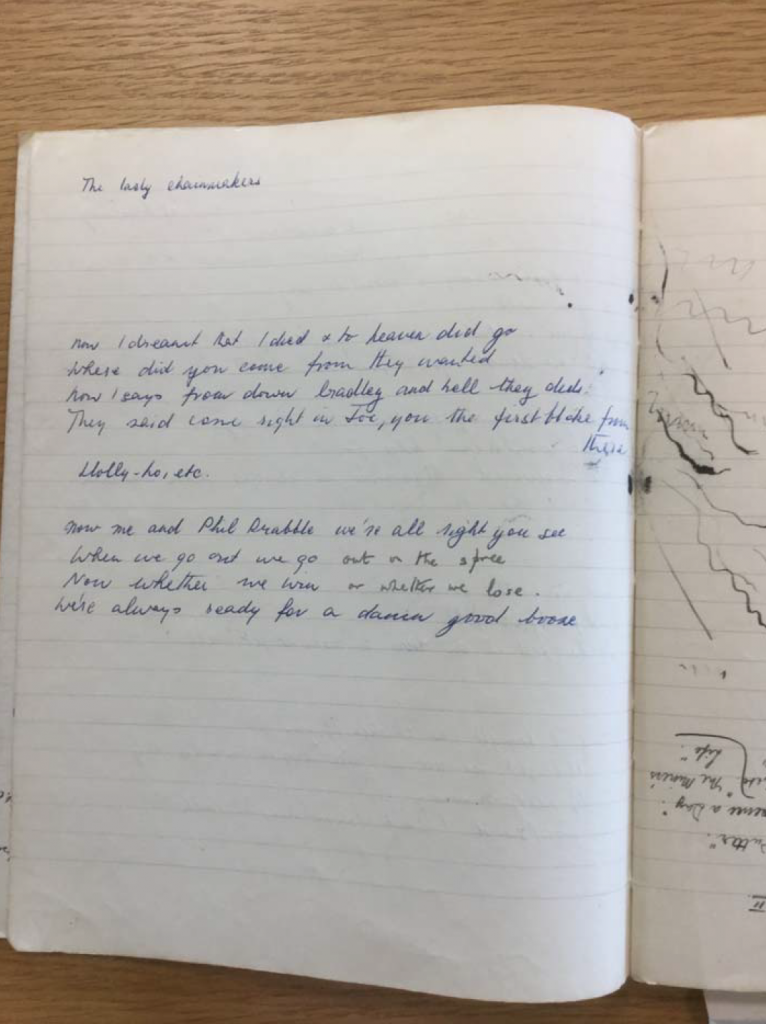

While we were unable to find further details on the collection of the song, the crowning glory of Pam’s trip to the Library of Birmingham that day was undoubtedly the discovery of Elizabeth Thomson’s notebook, in which the handwritten lyrics of ‘Holly Ho’ had been taken down for posterity.

If you scroll to the bottom of this page, you’ll find the set of lyrics I used in the recording of my song. It’s worth noting that at least one and a half verses exist in Elizabeth’s notebook that hadn’t made it to Roy Palmer’s publication. This is probably due to the missing punchlines.

Another two verses appear in Palmer’s book which are not taken down here. He explains that they were collected from a Mr Harper of West Hagley, about five miles from Cradley Heath. I like to imagine that the locals would’ve stumbled down the tracks over the following weeks and the song would’ve cross-pollinated with other versions that popped up around the area.

While Elizabeth Thomson felt that this was an example of a Black Country song, it is of course possible that it travelled to the region from elsewhere. When I started playing this song, my good friend and fellow folkie, Nick Hart, sent me a recording that he had of Geoff Ling singing it in Blaxhall, Suffolk. Whether the song migrated to or from Cradley Heath we can’t be sure, but one thing was certain: the final verse on the Suffolk version was simply too good to be true, so I tacked it on to Joe Mallen’s. It’s always the last verse of my gig, and I love sending the audience home with these words ringing in their ears.

To market, to market with my uncle Jim

When somebody threw some tomatoes at him

Now, tomatoes are soft and they don’t bruise the skin

But that’s not the case if they’re still in the tin

I like to think Joe would’ve approved.

Holly Ho and Phil Drabble

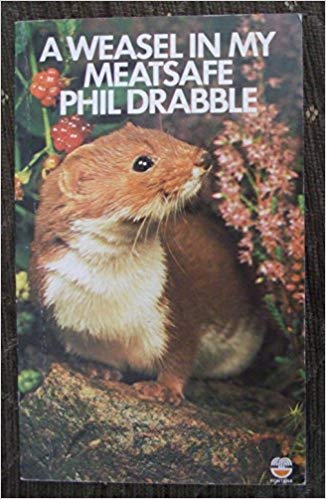

As I mentioned earlier, Phil Drabble is a name in his own right, and one that almost seems peculiar in the context of this song. Many older readers will remember him as the presenter of One Man And His Dog. A historian with a passion for his beloved Black Country, he wrote several books on the area, including the never-to-be-forgotten, There’s a Weasel in My Meatsafe.

As seminal as that classic may be, it’s his 1952 tome, The Black Country, to which we now turn. This was the final piece of the puzzle, and may will be the start of another song-finding journey for me.

As you will have heard in the recording embedded at the top of this page, Phil Drabble makes an unannounced and rather jarring appearance in the penultimate verse. Here he is, staggering around the pub, everyone and anyone’s drinking buddy. Not exactly what you might imagine from the steady voice of the sheepdog trials, 1976-1993.

But here on page 196 of the aforementioned book, we find Phil enshrining Joe Mallen and his Cross Guns pub for eternity. We even find a couple of songs that Phil seems to have taken down on a visit, not including ‘Holly Ho’ (these are ‘The Tramp’ and an untitled song that bemoans the workhouse as the inevitable final resting spot for the aged).

The description is fabulous, putting you right there in the room, so I’ll leave it to Phil to explain…

“I usually call at Greg’s, at Wednesfield, on my way home from a Sunday morning’s ferreting, and I meet the folk coming straight from church, to celebrate a good sermon, I gather, or to wash down the dust of a bad one.

“Whatever your taste, there is surely a “house” to suit it; a house where you will meet kindred spirits, where good beer comes second to good company. In the old days they went even further, and it was common to have not only a singing licence but a little stage as well. The Old Cross Guns at Cradley Heath is a typical example. Nowadays it’s famous for being the centre of all Stafford Bull-terrier men the country over. Joe Mallen, who kept it until recently, is known because he owned Gentleman Jim, the most famous Stafford there ever was, and nowadays nobody thinks of the place as other than the hub of “the fancy”. But where the old piano stands now, in the corner of the bar, was once a low stage, and regular concerts were held. Certain men specialized in going from pub to pub playing the piano, but otherwise the customers themselves provided all the turns. Some of them can still reel off verse after verse of the old songs and ballads, as if they only sung them yesterday. Joe often regales me for half and hour at a stretch, and the interesting thing is that the words and sense mattered far more than the tune. Indeed, there seem to have been a few stereotyped tunes which did service for a far larger repertoire of words.”

While all of these artefacts and documents belong to a much older time, I can’t help but feel that there are more songs there in the Black Country to be discovered yet. Maybe someone with more time on their hands, or a burning love of these authentic old gems, may one day get around to digging further.

Holly Ho, ft Nick Hart & Mikey Kenney

As mentioned above, my good pal, Nick Hart, picked up on my interest in this song early on and furnished me with an alternative recording. However, it’d be disingenuous of me to pretend that that’s all Nick did. Like a lot of people singing traditional folk songs at the moment, Nick’s recordings and style had an immediate effect and influence on me, and I’m acutely aware of how obvious that is on the way I play this song.

With that in mind, I asked him if he’d be a part of the recording. And since the style I’m playing in is so similar to his, I thought it best to ask him to add something else – he’s such an annoyingly talented multi-instrumental fellow, after all. So Nick recorded a melodeon part, giving the instrumental part of the song something almost cajun! Well, if the folks at the Cross Guns felt they could add their own thing, why shouldn’t we?

I’d also been having some great chats about canal songs with the wonderful fiddler and ethereally-voiced Mikey Kenney. (There aren’t many people in this world you can have great chats about canal songs with, so when you find them, you grab them and cling to them dearly.) Mikey was interested in ‘Holly Ho’, so I invited him to come and record with us. As with Nick’s additions, time and distance conspired so that we couldn’t get together in the same studio, so I sent him the recordings and he added parts in his studio, following Nick’s ornamental lead and adding those beautiful flourishes that tie up the end of the song.

There was an almost jigsaw-like process to recording the track that I felt wholly suited the song’s history and origins. Hopefully we’ve done Joe Mallen, Phil Drabble and the gang justice. Let us know what you think.

‘Holly Ho’ – Lyrics

Well, I know a song and a peculiar song

And if you would listen it won’t take me long

The rhyme’s very pretty, I’m sure you’ll agree

So no doubt you’ll all sing this chorus with me

Holly ho

Holly ho

Fol-de-rap fol-de-doodle da day

Well, I says to my sweetheart the other day

What dost thou want for thou’s birthday

She answered me, “diamonds”, so straight there and then

I gave her the Ace, the King, Queen, Jack and Ten

Well, the lady chainmakers have all gone on strike

For the owners they think they can pay what they like

They works ’em so hard both night and by day

And for it they gives ’em such terrible pay

Well, I dreamt that I died and to heaven did go

“Where dost yow come?” from they wanted to know

When I says, “I come from Cradley”, well how did they stare

They says, “You better come in, John, yowse the first bloke from there

Well, me and Phil Drabble, we’re alright you see

‘Cause me and Phil Drabble goes out on the spree

And whether we win or whether we lose

We’re always ready for a good drop of booze

To market, to market, with my Uncle Jim

When somebody threw some tomatoes at him

Now, tomatoes are soft and they don’t bruise the skin

But that’s not the case if they’re still in the tin

Huge thanks go to Pam Bishop for her help in researching ‘Holly Ho’ and much else. I’m also grateful to my other correspondents, each noted here.

Leave a Reply