What a weird little song this is, and quite startling in subject matter, too. As is the wont of many people developing an interest in traditional folk songs, I recently began investigating the songs from the area I come from – Birmingham and the surrounding West Midlands. Hardly a glamorous place in times gone by, the songs that really leap out out of the archives tend to be unrelentingly grim, or at the very least clothed in the thin veil of black humour.

In truth, many of them wouldn’t really class as traditional folk songs at all, having featured originally on broadsides or the music hall stage. This seems to be a relatively common occurrence in the larger cities at the time, as industrialisation and myriad social injustices gave the inhabitants something to come together and rally against. That’s not to say all Birmingham songs are of this nature. The wonderful recordings of the old Digbeth singer, Cecellia Costello, attest to the wide variety of tunes sung in her youth: everything from fairly common songs of love and romance, right through to snippets of local legend – Peaky Blinders fans take note…

https://twitter.com/JonWilksMusic/status/955735109205970944

https://twitter.com/JonWilksMusic/status/955735111915499520

A great place to start for anyone looking for old Birmingham songs is the Topic Records collection, The Wide Midlands, which brought together a collection of reasonably robust tunes and ballads, a smattering of spoken-word musings on topics including local law and the world’s biggest Aston Villa fan, and a few truly awful songs that probably won’t ever see the likes of day again (I’m of the firm belief that Darwin’s survival of the fittest theory applies, thankfully, to folk music, too).

All are delivered in almost comically strong Brummie accents, which prompts me to think that an interesting debate could be had on the necessities of needing to sing local songs in local dialects (take a bow, Ewan MacColl). Having lost most of my Birmingham accent years ago, I feel a bit of a fraud putting it back on again, so I tend not to, which subsequently leads me to worry that I’m cheating the songs in some way. I probably shouldn’t feel too guilty about that, since nothing can change the fact that these songs and I share, roughly, the same place of origin. That one of has long since replaced “yam” with “I am” is neither here nor there.

Click to discover other ‘Brummagem’ songs…

- ‘I Can’t Find Brummagem’

- ‘Colin’s Ghost’

- ‘Adieu, Adieu’

- ‘The Brave Dudley Boys’

- ‘There Was An Old Man Came Over the Sea’

One of the things that strikes me about the old songs of Birmingham and the West Midlands is that so few people seem to have performed them (other than a handful of Birmingham-based singers). Maybe that has something to do with the aforementioned dialect hurdle, or maybe it has something to do with the fact that non-Brummie folkies of the revival period may have avoided the city altogether, and therefore never heard any. Ian A. Anderson of fRoots told me recently that he almost never gigged there back in the 60s, and that most people would simply swing around the city on the outer ring-road, heading to folk clubs north and south of Brum, but never in it. A nice-sounding theory, perhaps, but J P Bean’s fantastic Singing From The Floor tells us that, at the height of the folk boom in the sixties, the folk club at Digbeth Civic Hall was the country’s biggest, with 400 paying customers every week. Somebody must’ve been playing there.

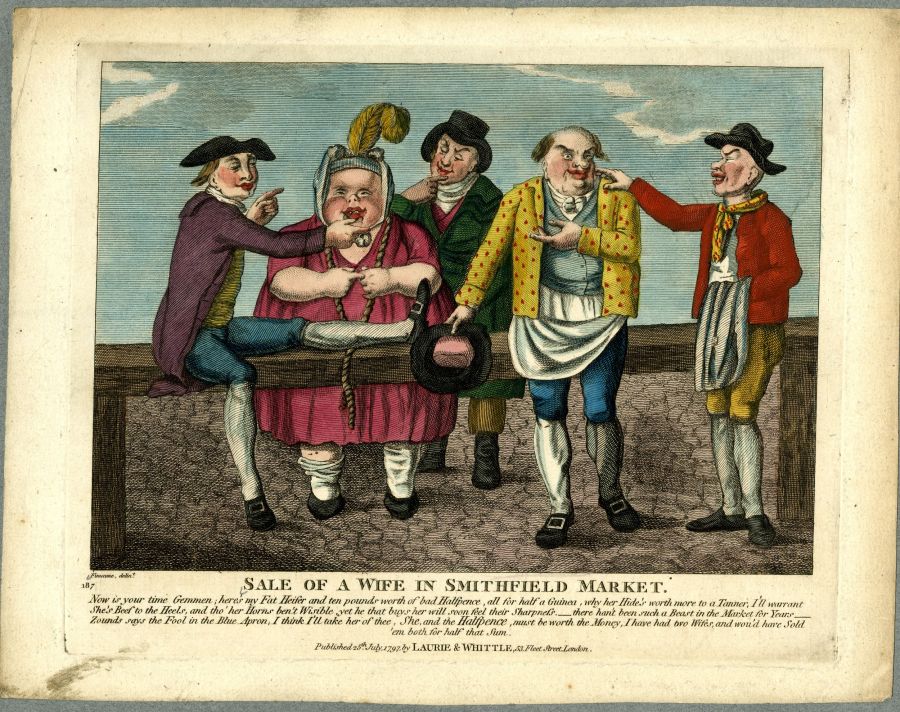

Perhaps it’s simply that many of the songs deal with themes that are decidedly unpleasant. Take this song as a case in point. ‘John Hobbs’ [Roud 21966] is a fairly pristine example of what were known as ‘wife-selling songs’ – and, yes, they deal with exactly what the genre title suggests they might. That several of them were collected in the Midlands points rather damningly to the fact that wife-selling was a common enough business in that neck of the woods.

For evidence, as well as the lyrics and a fragment of melody (albeit one that only comes ‘recommended’), we turn to Jon Raven’s snappily-titled tome, The Urban and Industrial Songs of the Black Country and Birmingham (1977).

“Black Country wives do not appear to have been weak and timid creatures. They accepted the traditional role of a wife but retained much of their individuality and were often as brutal and primitive in outlook as their husbands. But what if a husband and wife did not see eye to eye? Legally they were unable to obtain a divorce without invoking a special Act of Parliament, a protracted and expensive business. Because of the situation, custom of wife-selling had been popular long before the Industrial Revolution, and was first legislated against in the reign of King Canute.”

The common practice was for the husband to place a halter around his wife’s neck and lead her to market, where a ticket was purchased in order for the sale (nay, ritual) to commence. She was then led around the market several times (“a custom that was believed to legalise the proceedings”) before being auctioned off.

As depraved as this may sound to modern sensibilities (and, indeed, it sounded pretty depraved in the 19th century, too, with one newspaper noting, “We could mention a way in which a rope might very properly reward the persons concerned”) the outcome was not necessarily as miserable as it might appear. The wives were often just as keen to get out of the marriage as their want-away husbands, and on many occasions the setup simply allowed for both parties to commit adultery in what they optimistically hoped might be the eyes of the law (the wives’ lovers, if they existed, would come to market and pay to take them away – an arrangement that ultimately suited everyone and was considerably cheaper than divorce).

Indeed, this little racket became so problematic that in May 1790, the Birmingham Aris Gazette was moved to publish this little slip of advice:

“As instances of the sale of wives have of late frequently occurred among the lower classes of people who consider such sale lawful, we think it right to inform them that, by a determination of the courts of law in a former reign, they were declared illegal and void, and considered as mere pretence to sanction the crime of adultery.”

This relatively light twist in the tale may explain, to some extent, the reason why several of these wife-selling songs amount to little more than musical banter. ‘Bandy Leg Lett’, collected in Bilston near Wolverhampton, is typical in that it depicts the husband as something of a cuckhold – an object of public ridicule – who lets his wife “have all her own way”:

Her swears like a trouper

And fights like a cock

And has gi’n her old feller

Many a hard knock

So now yo’ young fellers

As wanting a wife,

Come and bid for old Sally

The plague of Lett’s life.

At 12 in the morning,

The sale’ll begin;

So yo’ as wants splicin’

Be there wi’ yer tin

‘John Hobbs’, on the other hand, is as dark and as sinister as the practice itself must have been for most people, although this particular account isn’t nearly as straightforward as it seems. The earliest collected version – a broadside – dates back to 1811 (when it was performed on stage by a Mr Lovegrove, “with unbounded applause”), and it seems to have been published frequently up until about 1838, suggesting that it must’ve been quite a hit in its time. A version was also collected by Janet Blunt in Northamptonshire (or Shropshire) in 1907 from the singing of either Mr or Miss Glover (it all depends on which record you’re looking at).

So, what of John Hobbs? Having taken his wife, Jane, to market, he finds that nobody wants to buy her, largely due to her understandably bitter disposition. Maybe through frustration or maybe due to severe humiliation, John Hobbs takes the rope from around his wife and hangs himself with it – quite an extreme reaction, even by the standard of most folk songs. For those who might hope for a happier ending, a variant finds the wife cutting him down and agreeing to work through their differences. Their marriage counsellor must’ve been exceptional.

Lyrics to ‘John Hobbs’

A jolly shoemaker, John Hobbs, John Hobbs

A jolly shoemaker, John Hobbs

He married Jane Carter,

No damsel looked smarter;

But he caught a tartar,

John Hobbs, John Hobbs

He caught a tartar, John Hobbs

He tied a rope to her, John Hobbs, John Hobbs

He tied a rope to her, John Hobbs

To escape from hot water

To Smithfield he brought her

But nobody bought her

Jane Hobbs, Jane Hobbs,

They all were afraid of Jane Hobbs

“Oh who’ll buy a wife?” says Hobbs, John Hobbs

“A sweet, pretty wife” says John Hobbs

But somehow they tell us:

Those wife dealing fellas

Were all of them sellers

John Hobbs, John Hobbs

And none of them wanted Jane Hobbs

The rope it was ready, John Hobbs, John Hobbs

“Come give me the rope!” says John Hobbs

I won’t stand to wrangle

Myself I will strangle

And hang dingle dangle

John Hobbs, John Hobbs

He hung dingle dangle, John Hobbs

Leave a Reply