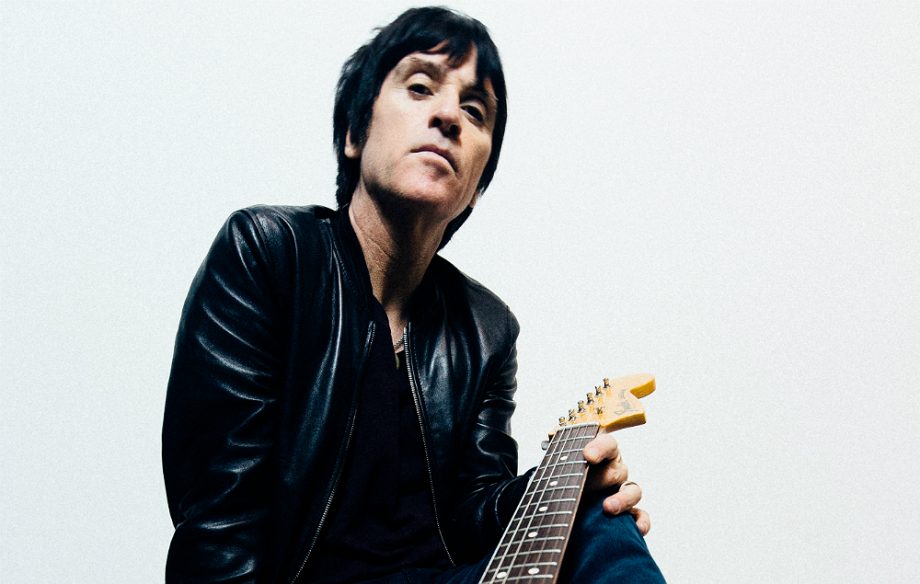

In my experience, the best interviewees have a tendency to ramble, and in this respect Johnny Marr is right up there with Sir Tom Jones. Obviously infatuated with his subject, Marr is fast becoming the man the magazines go to when they need a musicologist’s point of view. Since his early teenage years, he has lived and breathed music, and his encyclopaedic knowledge of rock and (more specifically) pop was an essential part of the foundations on which The Smiths morphed into the most important British group of their era.

As he prepares to release The Messenger, a debut solo album after 25 years of playing on records for other people, he talks to The Autojubilator about the artists he once emulated in the bedroom mirror, the development of his latest songs, and some of the more surprising collaborations that have taken place during his 30 years as a professional musician.

“I’m always doing what I call ‘producing with my feet’.”

I want to start off by going back to the early days after The Smiths, when you developed a reputation as a gun for hire. Is it true that you briefly joined Paul McCartney’s band? Did that really happen?

I didn’t do a recording session with him as such, but we did get together for a good long eight-or-nine-hour day, and just played and played and played very intensely, really loudly. Which was pretty great, obviously. He was pretty good! He can play that bass and sing pretty well, I must say. That was a fun time. That was pretty much the first thing I did when The Smiths stopped being together. I’ve seen him a couple of times since. We’ve not played together, but he’s always very friendly and very gracious.

Do you remember what you played?

Yeah, man! I remember everything about it. We played ‘I Saw Her Standing There’, ‘Twenty Flight Rock’, ‘Tutti Frutti’. I got him to play ‘Things We Said Today’, and I think we played some Wings stuff. ‘C-Moon’, I remember. That was fun. He and I were singing harmonies on ‘I Saw Her Standing There’ — that was a pretty good moment, too. I was only 23, maybe 24.

Had you grown up a big Beatles fan?

You can’t really avoid The Beatles if you’re breathing air and you’re a musician, I don’t think. The interesting thing was that, understandably, he likes to play the music that inspired him when he was a kid, when he was starting out. So there was a lot of Eddie Cochran — ‘Twenty Flight Rock’, ‘Come On Everybody’ — and I think he was surprised that I knew that stuff, because obviously it was made before my time, but I’d checked out a fair bit of rockabilly before The Smiths had formed. It was quite a popular movement, so I knew a bit of Scotty Moore and Chet Atkins — that kind of stuff. I think he was using a lot of the songs that were touchstones for him when he started out.

What was that session intended to achieve?

I think he was just sort of checking me out, because he’d liked what I’d done. The Smiths had asked Linda to play and sing on The Queen Is Dead album, which sadly she wasn’t able to, so he was aware of us. I think he liked the way I played, so that was cool.

You didn’t get to jam on any Smiths tracks with him, then?

Nah. I don’t think either of us would’ve been bothered about that.

I’m interested in your position as a British guitarist — where you see yourself fitting in the line up of the greats.

You know, I think to talk about myself in those sort of terms would make me uncomfortable, really. I think it’s not really my job. I don’t really like musicians who talk about themselves. It seems to have an aspect of self-mythologising, to be honest, and I think I’m too close to living my own life and trying to be a person and a good musician to stand outside it and talk about myself in those terms. It feels a little distasteful to me, somehow.

Do you see yourself following a certain kind of aesthetic, though? I get the impression you might identify more with George Harrison than Eric Clapton, say.

Well George Harrison has always been one of my favourite guitar players, and his approach to the song and creating little parts and moments in records is more something that I can relate to, and along the lines of how I see myself, sure. Out of respect to the guitar greats who came out of the blues rock boom in the 60s, you have to hold your hands up and show that respect. But unfortunately for them, the legacy they started somewhat mutated throughout the 1970s, when I was growing up, into other stuff that wasn’t really about my age group. But George Harrison’s more musical, composed kind of approach, rather than being particularly bluesy, was more my thing really.

“‘Layla’ is a pretty amazing track, I think. It’s kind of a thick guitar soup”

So you weren’t standing there in front of the bedroom mirror, ripping out the riff from ‘Layla’, then?

Oh, ‘Layla’ is a pretty amazing track, I think. It’s kind of a thick guitar soup, with a strange, haunted melancholia in it. Quite intense. Whenever I’ve heard that record, I’ve quite enjoyed it. I did plenty of standing in front of the mirror, but it was usually to T-Rex and the glam bands. Sparks, I liked a lot. ‘This Town Ain’t Big Enough for the Both of Us’ was an early single I bought, and that’s got really wicked guitar playing on it. And ‘All the Young Dudes’ by Mott the Hoople was a big record for me. Just trying to figure out the entire record was something that had a massive impact on me, and on the development of me as a guitar player and musician. I was really hooked on the harmonic change in the chorus from the A-Major to the A-Minor against the vocal melody. Those little devices were things that I would wander around and develop mystical notions about! Seriously! Or why ‘Metal Guru’ really sounded the way it did, and why it moved me in such a way, before I was able to understand the relationship between the backing vocals and the mellotron and the bass line and the chord change. All of these things were really mystical.

Do you still find yourself as fascinated by all that?

Yeah. When you hear something that touches you in a certain way, and you’re fascinated by it… once it has touched you, you can’t pretend that it hasn’t. I’ve lived my life in pursuit of those moments, and in my case, trying to create them for myself. Sometimes you reach it, and other times you happen to do really good stuff whilst you’re trying. Does that make sense? Cool.

The new album, The Messenger, is a really guitar-orientated album, and so it strikes me as being a return to your original love. Would that be a fair thing to say?

Yeah, I’d say that’s right. Partly because there were things that I didn’t overthink, and the considerations I did have, I was very focused on. I realised that there were some things that I should just be OK with and not focus on.

What were they?

It’s personal politics, almost, but in the case of this record certain things would crop up and it would be like, ‘My band don’t have that. My band don’t have that sound. My band wouldn’t use that sound.’ That was very useful.

How do you adapt to being a singer, or a frontman? As a guitarist myself, I find it incredibly difficult to play your riffs at the same time as singing Morrissey’s vocal lines, for instance.

Yeah, well I seem to be all right with it. When I’m playing Smiths songs live, if there are any bits that compromise the vocal then the guy who plays second guitar with me will take over at that point. I’ve got really into using pedals. I don’t use tons of pedals, but I change them from verse to chorus to bridge, and I’m always doing what I call ‘producing with my feet’. The technology has now caught up with me, in a very, very good way. You know, some of the devices you can get now, for someone like me, are heaven sent. I can switch from tremolo, to a certain kind of delay, to a backward sound. I mean… wow! I can really sound like the way I do on records.

Morrissey is on record as saying that The Smiths had the best of the both of you. I wonder how you feel about that as you sit here promoting The Messenger.

Well, he’s entitled to his opinion. People feel differently about everything. That’s probably quite a considered opinion on his part, so I’m not going to disagree with his right to say or believe whatever he wants. If that’s his opinion, then that’s fine, but I’ve done a lot since then and I think there’s a lot of songs that both of us have done outside of the band that are pretty good. So I think he’s selling the both of us short there.

Are there songs of his that you particularly like?

Erm, I don’t really want to get into that to be honest, because it’ll just be all over the internet like some silly rash.

Moving on, then… You’ve worked with a lot of great lyricists in your time — Morrissey, Billy Bragg — but this album really puts you into the spotlight as a wordsmith. Does that side of songwriting come naturally to you?

In a way, it’s just like music, or like when I’m doing a collage or taking photos. It’s the same kind of process. Some stuff just finds itself diving out of you, like ‘The Messenger’. The melody and vocal line for that song was exactly as I first sang it. I tried to sing it and re-sing it, and it just didn’t have the same spirit, and was a bit too straight and correct for me. ‘Upstarts’ I did in an afternoon, the whole song, start to finish. ‘Sun & Moon’ had a lot more verses, and when we went out to play it live I cut it down and rearranged it, added more words, and I enjoyed that puzzle. On ‘New Town Velocity’, I had a crazy deadline and really had to focus to write something that I could have overthought.

So I look back on every song, and I have a real fondness for the process. ‘Generate! Generate!’, believe it or not, took me the longest time because I was just trying to be too clever, and sometimes it wasn’t going quite right with the music. Like anything, even though it was a process, I really enjoyed getting it done. I don’t know if you’ve ever done crosswords? They’re not my thing, crosswords, but sometimes the stuff you put more work into is the most rewarding. Some stuff is a real breeze; some stuff is a craft. I like it all.

Johnny Marr’s debut solo album, The Messenger, is out on February 25. This interview was originally published on The Autojubilator.

Leave a Reply