‘We are singing about life, the great game of poesy. We are speaking of the truth from and at our eyes… the mode of nomadic life from the Tamashek people we love.’

– Ibrahim Ag Alhabib, Tinariwen

Back in 2010, I was working as the editor of Time Out in Abu Dhabi. On paper, it seemed like an unusual gig – a magazine dedicated to going out and enjoying the nightlife in a place that barely had any nightlife to offer. However, it was a case of right place, right time. During the two years I spent there, it went from being the fairly staid older brother to Dubai’s rebel upstart, and quite the place to live if you were into itinerant musicians. During the hot summers of each of those two years, the Womad Festival washed up on Abu Dhabi’s shores, and with it the chance to chat with and interview people I never would’ve encountered otherwise.

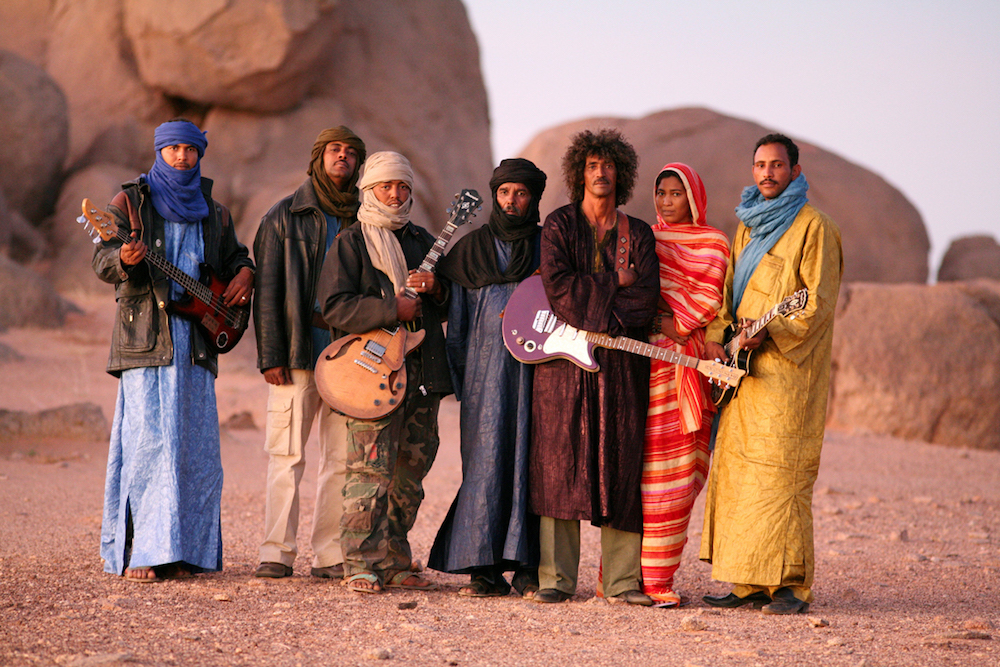

One such troupe was Tinariwen, and I recall a difficult conversation with their leader, Ibrahim Ag Alhabib – his English being only fractionally better than my nonexistent Touareg. Still, it’s not every day you get to interview a genuine desert bluesman, and although the wordcount was brief, it’s a memory that will remain with me for some time.

They count U2 among their fans, but they couldn’t be less like Bono’s crew if they tried. Founder Ibrahim Ag Alhabib tells Jon Wilks about Tinariwen’s hard past.

You probably haven’t heard of Tinariwen. Don’t worry. You soon will. They’ve already become the band to name-drop (Bono: ‘This kind of music is like a breath that I can feel;’ Thom Yorke: ‘I copied their style’), and industry bods are touting them as one of modern music’s most influential outfits.

However, their story begins not in the boardrooms of record companies, but in 1960s Sahara. Africa had just won its independence, but that victory took its toll on the nomadic Touareg people of the northern desert region. Unable to reconcile themselves with the new Malian government, they found themselves persecuted and violently suppressed. It’s a memory that haunts the Touareg still, and provides a catalyst to the Tinariwen tale.

‘When I was three or four years old, the Malian army came to take my father,’ says Ibrahim Ag Alhabib, the band’s founding member and lead singer. ‘They killed all our animals, but my family didn’t want to tell me what happened to my father. It was from the other children that I learned of the tragedy. From that moment, I was angry.’

Growing up in the itinerant refugee camps, Ibrahim, like many rebels the world over, found respite from his anger by playing traditional Touareg music – and soon other refugees joined in. ‘Our situation was lamentable,’ he says.

‘In exile we were wandering, not knowing where to go or what we could do. Playing together gave us motivation and enthusiasm to explain the reality of our people.’ Ibrahim eventually bought a guitar – an instrument he’d coveted since he saw one as a child in a long-forgotten cowboy movie – and fell in with a gang of similarly minded Touareg music junkies. They began playing an improvised fusion of Elvis, chaabi protest songs, Dire Straits and Algerian raï that, he says, helped them face up to the hardships of life. By 1980, they’d drifted into Libya, where Colonel Gaddafi’s new desert training camps promised them freedom by force. But as they came to the miserable realisation that Gaddafi was using them to consolidate his own power, Tinariwen’s desert blues gave voice to the Touareg’s disillusion.

Scratchy bootlegs passed from hand to hand, gaining the band European gigs in the early ’90s that helped them to strengthen their position abroad. But the band continue to give something back. ‘The shows we do in the desert, and the rehearsals for our album – these are good moments that help to give jobs around each activity.’

Before we depart, we’re keen to tackle that blues question. Carlos Santana has said that by performing Touareg traditional folk music, Tinariwen represent the sound that gave birth to the genre (‘Muddy Waters, BB King, Little Walter… this is where it all comes from… [Tinariwen] are the originators’). It’s quite a mantle to bear, so how does Ibrahim feel about carrying it? ‘The origins are different,’ he muses, ‘but the notes and the blue colours are the same. We are singing about life, the great game of poesy. We are speaking of the truth from and at our eyes… the mode of nomadic life from the Tamashek people we love.’ Unless we’re much mistaken, it sounds like them ol’ walkin’ blues again.

First published in Time Out Abu Dhabi, 2010.

Leave a Reply