‘John Riley’ is a common title, and an even more common character, in the canon of traditional English songs. He’s so ubiquitous, in fact, one might assume he’s a single character of great renown. However, as this article finds, he appears to be many men caught up in multiple stories, each belonging to a song family of their own. To find out as much as I could about John Riley, I spent hours traipsing through the Roud Index on the VWML website. And that’s where we shall start.

How the Roud Index works

What is a Roud number? Very simply, these are the individual numbers given to traditional folk songs by archivist, Steve Roud. Information regarding a song – the multiple times it was collected, who the source singers were, who collected it – lives beneath a specific Roud archive number. Therefore, it’s common to find a myriad of entries, often with a great number of variants on a specific title, all living comfortably under a single Roud number. In a sense, this means that each song belongs to a form of ‘song family’.

Setting ‘John Riley’ aside for a moment, let’s take Roud Number 1 as an example. The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, where the Roud Index is housed, lists 907 entries for this song. Multiple titles range across ‘Raggle Taggle Gypsies’, ‘Gypsy Davy’, ‘The Gypsy Laddie’, ‘Johnny Faa’, and plenty more. While the titles often seem wildly different, there are enough similarities in the content of the songs themselves, from variant to variant, to necessitate a listing under a single number. Again, to use the ‘song family’ concept, each variant could be seen a having descended from a single song or ancestor.

What is less common (although not quite a rarity) is to find a specific title living under multiple Roud numbers. ‘John Riley’ is a good example of that happening. To underline what I mean, on my album, Up The Cut, I perform a version that is listed as Roud 270. However, my friend, the folk singer Nick Hart, performs a song called ‘John Riley’ that is listed as Roud 10. Elsewhere, versions of ‘John Riley’ appear as ‘Young Riley’ and some 248 similar variants all listed under the number Roud 267. Just to confuse matters further, ‘John Riley’ (sometimes ‘George Riley’) turns up under Roud 264. In short, there are more John Rileys out there than this blogpost has time for. Tracking them all down would require me to change careers and become a professional John Riley obsessive. Not much money in that.

When is John Riley not John Riley?

As I mentioned above, at least three song families, or Roud entries, feature the title, ‘John Riley’. The version (Roud 10) that Nick Hart performs with Dominie Hooper on his album, Nick Hart Sings Nine English Folk Songs, actually belongs to a different song family altogether.

Roud 10 deals with the ‘Lord Randall’ song family, notable for a common refrain: “Where have you been, Lord Randall, my son?” The name in the refrain is interchangeable, and countless names may turn up in that little slot. When Bob Dylan transformed ‘Lord Randall’ into ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’, the name was replaced altogether with “blue-eyed” (“Oh, where have you been, my blue-eyed son?”). In the case of Nick Hart’s version, ‘John Riley’ fits the bill.

So, why is this not the John Riley we’re looking for? In short, as fine a John Riley as he may be, this young gentleman quite clearly belongs to Lord Randall’s family. His name appears to be something of a coincidence. By the time the version that Nick sings was collected (in Ely from John Darling, possibly Dowling, by Cecil Sharp on September 8th, 1911), that particular moniker had found its way into the verses. On that day he was John Riley. On any other day, he may well have been Lord Randall. Because he’s so often not John Riley in this version of the song, his discovery here feels like pure chance.

A better known John Riley

Perhaps the best known version of the song under the name ‘John Riley’ is the one performed by Joan Baez. This is catalogued as Roud 264, and just to confuse matters it also goes under the names ‘Pretty Fair Miss’, ‘The Single Soldier’, ‘Edward’, ‘The Brisk Young Sailor’, ‘A Fair Maid a Walking’, and many others. The latter title makes the most sense as it’s a common opening line – one of the key components that brings these variants together as a song family.

The strongest commonality is the narrative itself, which finds a young woman lamenting the loss of her beloved John Riley. When a new suitor arrives, her parents suggest that she forgets about the lost Riley, throwing her into several verses of quandary. Just as she’s about to lose it completely, the new suitor reveals himself to have been the missing John Riley all along. Maybe his intentions were to test her loyalty, and it’s one of those songs where you wish it would continue. The next verse would surely find her gathering her wits about her and giving him what for. What a sinister game to be playing!

The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library records around 650 entries relating to this particular ‘John Riley’, and it makes sense that it has become the better known version – this fellow has truly travelled far and wide. While it was collected across the UK, it seems to have taken particular hold from the Midlands down across the South, where it was commonly collected as ‘A Fair Maid a Walking’ (or something similar), as well as ‘The Broken Token’. Cecil Sharp collected versions (more on which in a moment), as did Henry Hammond (from Edith Sartin, distant relative of my good friend Paul Sartin, no less), as did Sabine Baring-Gould. It was also collected regularly across Ireland, where the name, ‘Lady in Her Father’s Garden’, seems to have taken root.

‘John Riley’ and Cecil Sharp

Once the song arrives in America, it spreads like wildfire, with particular focus around the Appalachian region. Sure enough, it’s one of those fascinating curios that Cecil Sharp found himself collecting on both sides of the Atlantic. Indeed, this song family goes a long way to demonstrating just how committed Sharp was, and it almost bookends his life as a collector.

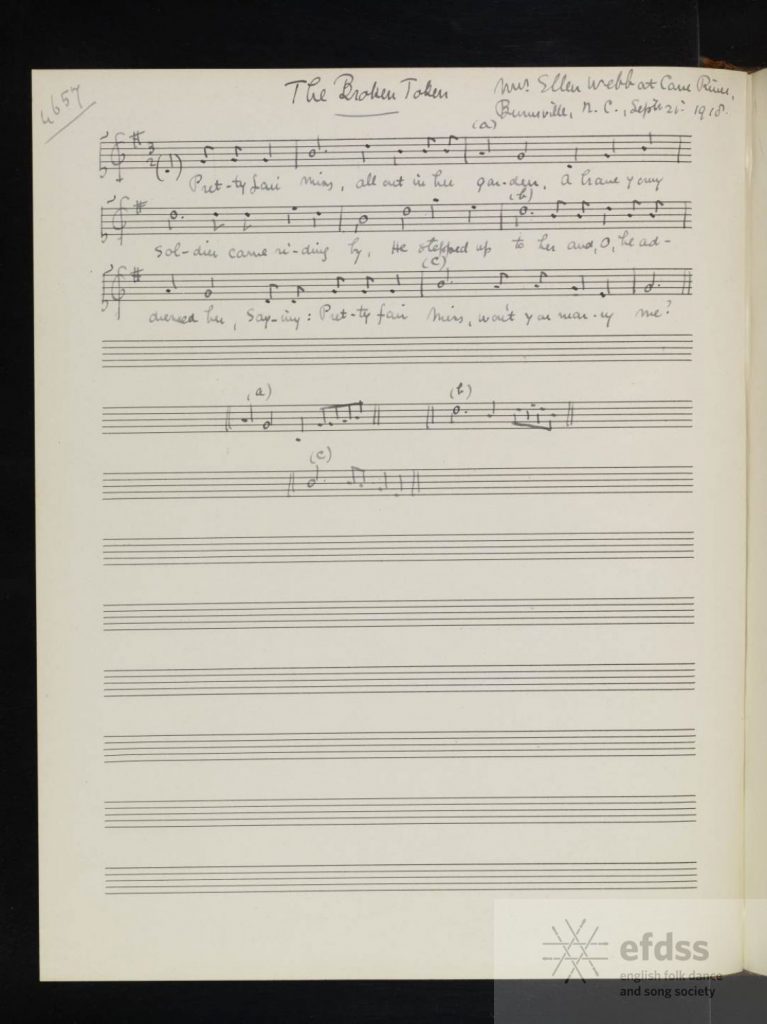

The VWML website records 79 entries relating Sharp to this song. (For the record, the earliest I can find on that website is Lucy White singing ‘The Broken Token’ to him on April 13th, 1904, in Hambridge, Somerset (the same place that he first heard John England singing ‘Seeds of Love’ – the first traditional song he collected – a mere eight months earlier). The last collection comes at the end of his visit to America, when he took down the manuscript below (from the EFDSS website), collecting ‘Pretty Fair Miss, All Out in Her Garden’ from Ellen Webb, Burnsville, Carolina, September 21st, 2018.)

Versions of Roud 264 have been recorded by countless 20th century singers, and more recently, too. As well as Joan Baez, you’ll find recordings on albums by Pete Seeger, Roger McGuinn and Judy Collins, Magpie Lane, The Demon Barbers, Josienne Clarke and Ben Walker, to name but a few.

One last ‘John Riley’ – an alternative version

Which brings me to the version I recently recorded. This is the John Riley I’ve been looking for.

Residing under Roud number 270, this is the version that most commonly tends to have the name you’d expect of it, albeit with countless different spellings. Sometimes the title is simply John Riley’s name, sometimes it contains his occupation or a hint of his fate to come (‘Riley the Fisherman’; ‘Riley’s Farewell’). In Ireland, he becomes ‘Willie Reilly’; in the States, ‘Johnny’ or ‘Jack Riley’. What’s clear is that, with 304 entries into the collection at the VWML, this version is roughly half as common as the one we associate with Joan Baez.

The difference, certainly in the version that I sing, has largely to do with narrative. The character may have the same name, but his intentions are less opaque. I learnt this version from recordings of the Staffordshire singer, George Dunn, collected by Roy Palmer on July 14th, 1971, and the narrative finds a woman in love with a man (John Riley) who is being hunted by her own father. Her mother warns her that the fearsome patriarch has gone out with his gun in the hopes of shooting Riley, and she gives the young couple some money with which to escape, “to Amerikay”. This being a traditional folk song, their ship gets hit by a storm and everybody dies. The father is left grieving his loss and (presumably, but not explicitly) his own stupidity.

Again, we find ourselves wondering a little about the final verse, which confuses matters this time by warning young women against running away to ‘Amerikay’, rather than condemning blood-thirsty fathers. I have often wondered whether to leave that verse out or not, but I’m interested in the morality displayed in these old songs, rather than editing them to suit a modern sentiment, and so I’ve left the version intact.

I suppose this raises a simple question: should we edit traditional songs or leave them as we found them? There are many reasons that one might pick or choose verses from here or there, or even write new parts in, to form “the ultimate narrative”, and with other songs I have done that (‘I Can’t Find Brummagem‘, being the most obvious example). However, I’m not sure that I’m a huge fan of editing songs to remove dubious intent or unsavoury moral character.

With both this song and ‘Mary Ashford’s Tragedy‘, I thought long and hard about removing verses that contain character behaviour or pronouncements that may be deemed inappropriate by modern standards. By removing what we feel to be uncomfortable and, instead, presenting a cleaned up version, I often wonder whether we simply lower the mirror that they hold up to our current age. These songs often stand as a warning – voices of experience calling to us over the centuries – so by cleaning them up do we not simply remove the warnings altogether? Do we make the assumption that we’re morally better, as a society, than the original singers of these songs? Do we not simply amputate the opportunity to debate, to evolve, to learn from the warnings? Doing so often makes me just as uncomfortable, so I tend to leave those verses in.

So, who was John Riley?

What’s fascinating to me, having been through the many versions of this song, is just how little is revealed of John Riley himself. He’s invariably something of a supporting character in his own song – occasionally the antagonist, sometimes a surprisingly passive figure, maybe a trickster, possibly a ghost, often an emaciated character not in control of his own destiny. In short: go looking for John Riley and you’re likely to find a set of vague character witnesses, none of which will leave you any the wiser.

How to play ‘John Riley’ on the guitar

I recently uploaded a guitar tutorial on how I play the guitar part for this particular version of ‘John Riley’, as recorded on my album, Up the Cut. You can find the video below. The tuning is CGCGCD with a capo on the 2nd fret. I’d love to see/hear how you get on. If you upload your own version, please leave a link in the comment section below.

Lyrics to ‘John Riley’ [Roud 270]

John Riley was her true love’s name

An honest man was he

He’s loved a farmer’s daughter dear

As faithful as can be

Her father he had riches but

John Riley, he was poor

Because she’s loved this honest man

He would not her endure

Oh mother dear, oh mother dear

Where shall I send my love?

His very heart lies in my breast

As constant as a dove

Oh daughter dear, I’m not severe,

And here’s a thousand pounds

Send Riley to Amerikay

To purchase there some ground

Soon as she’s got the money

To John Riley she did run

Saying on this night to have your life

My father’s charged his gun

But here’s a thousand pounds in gold

My mother sent to you

Go quickly to Amerikay

And quickly I’ll pursue

Soon as they’ve got the money

The next day they sailed away

But very quickly came a storm

That lasted all the day

The ship went down, all hands were lost

And her father grieved so sore

They found her in John Riley’s arms

Drowned upon the shore

And on her breast a note was writ

It’s written all in blood

Saying cruel was my father

Who went out to shoot my love

But let this be a warning to all you maidens gay

Never to let the lad you love

Sail to Amerikay

In researching the story of the traditional song, ‘John Riley’, I am in debt (as always) to the people behind the VWML website, as well as the superb Mainly Norfolk.

Leave a Reply